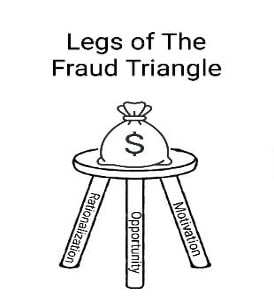

In the 1950’s in a dissertation at Indiana University, Donald R. Cressey and Edwin H. Sutherland first proposed the idea of what is now infamously known as The Fraud Triangle. Cressey was interviewing embezzlers, who he referred to as “trust violators”, trying to understand the circumstances that led them to first breaking that trust. His final hypothesis was condensed down to the three elements that he believed must be present for fraud to occur: Motivation, Opportunity, and Rationalization.

- Motivation: a perceived pressure, generally financial pressure, that makes the Trust Violator feel they must commit the fraud.

- Opportunity: because of the trust placed in them, the Trust Violator has the perceived opportunity to commit the fraud, and they feel they can do it without getting caught.

- Rationalization: embezzlers generally do not believe themselves to be criminals, therefore their rationalization must occur prior to the theft and is often part of the motivation.

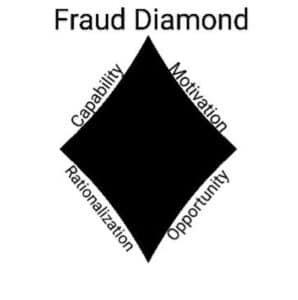

In the example of Suzie above, she had the capability to perpetrate this specific fraud because she input her own time into the timekeeping system and her . She could spend the majority of her work week at the circus, but as long as 40 hours were input into the system with a plausible description, she would be paid for them.

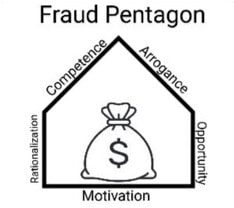

Back to Suzie’s example, her competence is the same as her capability discussed above, but her arrogance would come from the idea that even if she didn’t work the entire 40 hours she should be entitled to the pay because she was good at her job and she deserved it. She knew that she wasn’t supposed to input more hours than she worked, however with COVID-19 she felt that rule certainly shouldn’t still apply. Arrogance helps explain why Suzie decided to commit fraud, but Ashley, another secretary at the same company with the same set of circumstances did not commit fraud.

The question is, did we improve upon the Fraud Triangle? Or just muddy the waters? Is a Fraud Hexagon next? It is easy to see how losing even one leg of the Fraud Triangle would cause the entire scheme to collapse, but the more we add to it, the more convoluted it becomes. Cressey’s original hypothesis was intended to address “occupational fraud”, an internal fraud committed by someone within the organization taking advantage of their employment for personal benefit. He intentionally excluded from his research people who took jobs for the purpose of stealing. By adding a capability, beyond just opportunity, and an arrogance beyond just rationalization, are we taking this further than Cressey had ever intended, to external or predatory fraud?

It is also important to note that “the Fraud Triangle is a useful tool to help us understand why and how people commit fraud, but it’s not a scientific theory.” as John D. Gill says in his article The Fraud Triangle on Trial. Especially if you are taking a fraud case to court, the judge isn’t likely to agree with you based solely on the grounds that the three legs of the fraud triangle are present. Just because someone can, doesn’t mean that they will commit fraud. It’s impossible to know why two people in “almost” the exact same situation would make different choices. When dealing with fraud, you must remember that each case is as unique as the embezzler themselves and that uniqueness is why two people are never in the exact same situation. Although the fraud shapes provide a useful framework to help with fraud analysis, they do not prove fraud on their own.

The partners at Capstone Forensic Group all hold the CFE (Certified Fraud Examiner) credential and are happy to help review your evidence and show if elements of fraud are present in your case.