By Jeff Compton and Michael Shapiro

June 29, 2018

For professional practices and owner managed firms, an understanding of personal goodwill is vital to understanding the fair market value of the business. Specifically, with multiple owners, the existence of personal goodwill can cause the fair market value allocable to a given owner to be materially different than his or her respective legal ownership percentage. Regardless of the number of owners, personal goodwill can cause the value of the enterprise to be materially different if it is not transferrable. Distinguishing between personal goodwill and corporate goodwill should occur in any business valuation, especially in professional practices and owner-managed firms.

What is Personal Goodwill?

Personal goodwill is the value associated with and stemming from an individual rather than the firm. It is the value of the excess cash flow that is attributable to an individual from returning customers or customers who seek out the individual.[1] Consequently, it is the value attributable to those customers seeking out the individual, choosing to travel with the individual to another firm absent a restriction. Corporate goodwill is the goodwill value associated with and stemming from the corporate entity or firm as a whole. It is the value of the excess cash flow that is not attributable to an individual practicing professional or owner.[2]

With the growing importance of intellectual property including trade secrets, “know how”, etc., as well as the historical importance of personal relationships, the individual owner or employee often has an effect on the fair market value of the firm which should be identified as personal goodwill attributable to that individual rather than corporate goodwill belonging to the firm and its owners.[3]

As professional service providers and business owners, our work is based on relationships. Customers either choose us personally, our firm, or a combination of both. When a professional services practice is sold, most of the value likely arises from intangible value[4] instead of tangible assets.[5] This intangible value includes specifically identified intangible assets[6] as well the non-specific residual intangible value defined as goodwill.

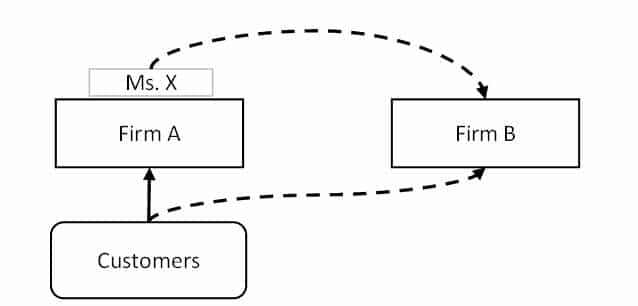

The value of those intangible assets depends upon the revenue and consequent profits of the practice or business, which depend upon the continuity and level of revenue and consequent profits of a firm arising from the relationships between the firm (including the owner and employees) on the one hand, and the customer on the other. If the continuity of revenue depends mostly on the person obtaining the work, that person has personal goodwill, and consequently more value of the firm is allocable to her. If all customers follow a person to another business, then by deduction the only value left of the prior firm would be the tangible assets. For example, as shown in Figure 1 below, Ms. X went from Firm A to Firm B, bringing with her all her customers. If no other individuals bring in customers to Firm A, the remaining value of Firm A is its tangible assets, and Ms. X rather than the firm owns, absent restriction on taking customers such as a non-compete, substantial intangible value through personal goodwill. Note that her personal goodwill is independent of what her percent ownership, if any, of Firm A was.

Measuring Total Goodwill

Goodwill is a residual value. It is the value that is left over after all other contributors to value have been accounted for.[7] That is, goodwill is the value of cash flows not specifically identifiable to any other tangible or intangible asset.

In valuing a business, three approaches should be considered. The income approach is based on the fundamental theory that value is derived from expected future benefits.[8] Cash flows stemming from all of the tangible and intangible assets are projected and discounted to the present value. The market approach compares the subject business to comparable business that are transacted in the marketplace, also resulting in the value of the entire firm. The value of goodwill stems from those cash flows that are not attributable to any other asset.

The asset approach requires the analyst to value each asset and liability. This includes tangible assets, and intangible assets for which value is not derived from the physical characteristics of the assets (e.g. favorable lease agreements, patents, trademarks).[9] Technically, intangible assets can be segregated among various specifically identified components, generally falling under three categories.[10] These categories are customer based intangible assets, such as customer lists and customer contracts; workforce based intangible assets, such as the trained and assembled workforce; and intellectual property based intangible assets such as patents and trademarks. An analyst using the asset approach should work to identify and value these separate intangible assets. Because goodwill is not separately identifiable, an analyst can use an excess earnings method to calculate goodwill for the asset approach. Alternatively, the difference between the asset approach (without the excess earnings method) and the income and/or market approach gives the residual value of goodwill after separately identifiable intangible assets are segregated.

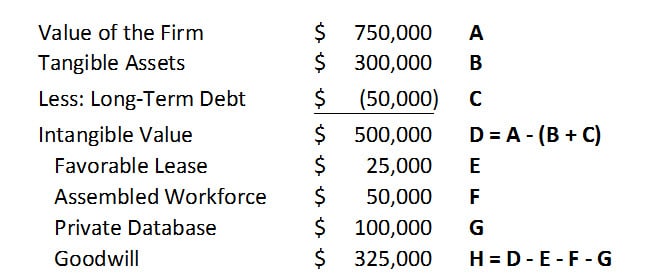

As an example, imagine a hypothetical CPA firm with $1 million in annual revenues. An appraiser determines the value of the entire firm to be $750,000 based on a combination of the income and market approaches. The appraiser also determines the fair market value of all tangible assets to be $300,000 and the fair market value of the long-term debt to be $50,000. The intangible value of this CPA firm is therefore $500,000.[11] The appraiser identifies and values the following intangibles: a favorable lease agreement valued at $25,000,[12] the trained and assembled workforce, valued at $50,000,[13] and a privately owned database, valued at $100,000.[14] If that is the sum of all intangible assets that are separately identifiable and recognizable, the remaining value of $325,000 is the value of goodwill, which may be either personal goodwill or corporate goodwill.

As illustrated in the above example, goodwill is the residual value after all other tangible and intangible assets have been identified. Understood another way, it is the value of the cash flows that are not attributable to any other asset. It is the subset of intangible value which cannot be separately identified. If an asset can be separately identified, recognized, and quantified, it is not technically goodwill.[15] Therefore, if no effort is made by an analyst to identify and quantify the value of intangible assets, the value of goodwill may be overstated.

Allocating Goodwill: Measuring Personal Goodwill

Once goodwill is identified, it must be allocated. Goodwill is either related to an individual or related to the firm as a whole. That is, total goodwill is the sum of personal goodwill and corporate goodwill.[16] Personal goodwill is the value of the firm that is solely allocable to the individual. Because goodwill is the value of excess cash flow that is not attributable to any other tangible or identified intangible assets, personal goodwill is the value of that excess cash flow that is attributable to the individual person.[17] Corporate goodwill is the remaining excess cash flow that is not attributable to the individual.[18]

There are a number of factors to consider when distinguishing between personal and corporate goodwill. For example, personal goodwill is indicated by customers who contact the individual directly or referrals that are made directly to the individual; consequently sales depend largely on the individual. Corporate goodwill likely plays a larger role in firms in which customers have limited contact with specific individual, and in which referrals are made to the firm, and customers main point of contact occurs with the firm, not the individual.[19]

The most direct way to measure personal goodwill would be to ask customers of a professional practice or business their reasons for coming to that particular firm. Do they come for the individual person, or for some other reason not attributable to the person? Or is it some combination? Unfortunately, in many cases, it is not possible to contact the customers in order to ask these questions.

Another way to calculate personal goodwill is to subjectively allocate total goodwill based on an analysis of the factors (some of which are mentioned above) that determine whether there is more personal or corporate goodwill.[20] The multiattribute utility model (MUM) is another common method of subjectively allocating goodwill as personal or corporate based on applying weights to each factor for both its importance and presence in a particular firm.[21]

A more direct way of calculating personal goodwill is the “with and without” method,[22] in which an analyst values the firm twice: once with the specific individual(s) and once without. The difference in value will stem from the reduced cash flows as a result of the person hypothetically not working at the firm. This difference indicates the value of the cash flows that are in excess of the other tangible and intangible assets that are directly attributable to the individual; in other words, the personal goodwill. The major drawback of this method is that it may require heavy reliance on management to supply the information necessary to project how cash flows would be impacted by the hypothetical departure of the practicing person.

Personal goodwill may also be measured by looking at the value of hypothetical or comparable noncompete agreements. A noncompete agreement is one way to transfer the personal goodwill of an individual to the business. If a noncompete agreement exists between an individual and a business, that person is transferring some of his or her personal goodwill to the business because a hypothetical buyer would not have to be concerned about the possibility of losing customers to a departing employee.[23] The value of a noncompete agreement should equal the value to a firm of preventing an individual person from leaving and working with (or starting) a competing firm.[24] This value should roughly equal the loss to the firm if the person were to leave and compete. This loss to the firm of a hypothetical departure should indicate the value of those excess cash flows that are attributable to the particular person, that is, her personal goodwill. There are drawbacks here as well. First, not all noncompete agreements are the same, and the terms and enforceability can have a large impact on value. They also may understate the value of personal goodwill to the extent the probability of departure of less than 100% is accounted for in the calculation of the value of the noncompete.[25] Furthermore, when considering the value of a hypothetical noncompete agreement as a measure of personal goodwill, it is important to also consider a hypothetical employment agreement wherein an individual not only agrees not to compete, but also agrees to help transition customers to the business under a new owner. A noncompete agreement is simply a prohibition, whereas an employment agreement encourages cooperation of the individual. Both of these agreements help transfer personal goodwill from the individual to the business.

All methods of valuing personal goodwill require a degree of subjectivity and professional judgment. The key to all these methods is that they are trying to quantify the residual value of a firm that is attributable solely to the person rather than the firm.

Effect of Personal Goodwill on Allocation of Value

Whatever method used to calculate personal goodwill, that value is not allocable to the firm as a whole. If the person were to leave, the firm would not retain that value. Think about the example at the beginning of this article. If all of a firm’s customers followed one individual from Firm A to Firm B, Firm A would have little value left over after the individual moved.

Note, personal goodwill exists separately from key person discounts[26]

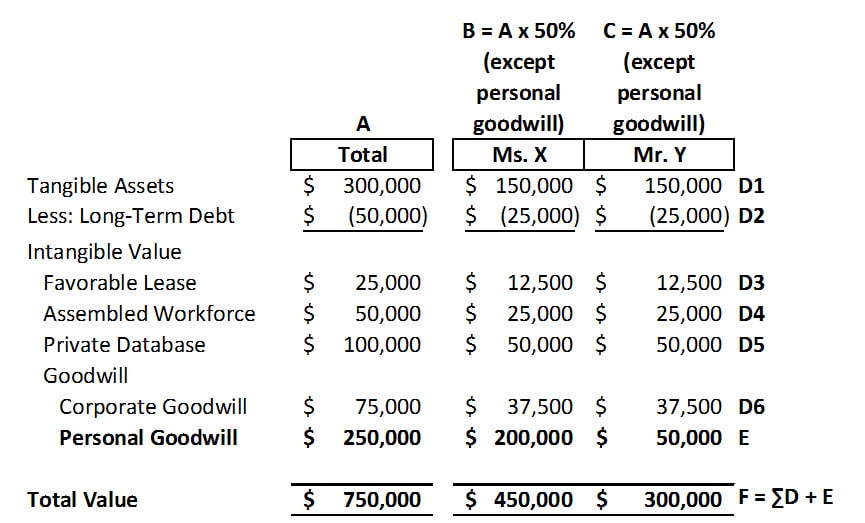

It is important to understand how the amount of personal goodwill can affect the allocation of value.[27] If personal goodwill is large, the value of a firm allocated to a practicing person may be greater than her percentage ownership in the firm. As an example, consider the CPA firm valued at $750,000, referred to earlier. Assume Ms. X and Mr. Y each have a legal ownership of 50% of the firm. The value of all tangible and separately identified intangible assets are allocated to each of them equally. Similarly, the value of corporate goodwill is allocated equally, as both individuals are 50% owners. Now, to illustrate the impact of personal goodwill on the allocation of value, imagine that Ms. X has personal goodwill of $200,000, and Mr. Y has personal goodwill of $50,000, as calculated using one or more of the methods described above. As shown in Table 2, if we divide all other assets and liabilities evenly, according to their ownership interests, and divide personal goodwill as described, the value of the $750,000 firm allocable to Ms. X would be $450,000, and the value of the firm allocable to Mr. Y would only be $300,000.

Alternatively, using these same assumptions, one could allocate value by removing the total personal goodwill, allocating the remaining value of $500,000 according the ownership percentage, and then adding back personal goodwill as calculated. In either case, we can see that Ms. X ends up with 60% of the firm’s value (or $450,000) being allocated to her, despite owning 50% of the firm. Accordingly, Mr. Y only ends up with 40% of the firm’s value (or $300,000) being allocated to him, despite his 50% ownership. Note that if both Ms. X and Mr. Y are selling the firm, and do not have any agreements to transfer their personal goodwill, the value of the firm that a hypothetical buyer would be willing to pay would be $500,000 (i.e. the $750,000 total value less the non-transferable personal goodwill of $250,000). Personal goodwill is just that: personal. It does not belong to the firm as a whole unless there are agreements in place to help transfer that goodwill. A hypothetical buyer will not by willing to pay for value that he or she will not receive.

As we can see, personal goodwill is especially important in owner-managed businesses and professional services firms, in which customer relations are relatively more important and there is a large amount of intangible value and goodwill. If an individual is responsible for most of the cash flows of a firm, that person will have greater personal goodwill. This personal goodwill is solely allocable to the individual, irrespective of his or her legal ownership of the firm. The remaining value is allocable to all shareholders of the firm in proportion to their stated ownership. Therefore, the value of a firm to each shareholder may not be equal to their stated ownership. If there is a significant amount of goodwill, and a significant difference between the allocation of personal goodwill and the percent ownership of a company, there may be a large difference in the allocation of overall firm value and legal ownership. In the case of other firms in which there is little or no personal goodwill (such as large commercial firms) the difference between legal ownership and allocable value may be negligible or may not exist. Individual shareholders should recognize that they may realize a value that is higher or lower than their ownership because of personal goodwill. Absent an agreement to effectively transfer the personal goodwill, the fair market value of the firm goes down because the hypothetical buyer will not pay for something not transferred.

[1] Wood, David. “Personal Goodwill in Search of a Functional Definition.” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Page 40

[2] Ibid. Page 41

[3] Note, while any employee may have personal goodwill, it is more common in practicing professionals and owner-managers.

[4] Pratt, Shannon. Valuing Small Businesses and Professional Practices. Second Edition. 1993. Page 389.

[5] Tangible assets are assets for which value is derived from the physical characteristics of the asset (e.g. cash, accounts receivable, real and personal property, and inventory). See Reilly, Robert and Robert Schweihs. Valuing Intangible Assets. 1999. Page 10

[6] Intangible assets are those for which value is not derived from the physical characteristics (e.g. licenses, favorable agreements, computer code, patents, trademarks, and assembled workforce). See Reilly, Robert and Robert Schweihs. Valuing Intangible Assets. 1999. Page 10

[7] ASC 805;

International Glossary of Business Valuation Terms;

Pratt, Shannon. Valuing Small Businesses and Professional Practices. Second Edition. 1993. Page 410;

Reilly, Robert and Robert Schweihs. Valuing Intangible Assets. 1999. Page 382

[8] Brealey, Richard and Stewart Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 1996. Page 73

[9] Reilly, Robert and Robert Schweihs. Valuing Intangible Assets. 1999. Page 10

[10] ASC 805 identifies a non-exhaustive list of 28 examples over five categories.

[11] $750,000 firm value – ($300,000 tangible assets – $50,000 long term debt)

[12] This may be valued as the discounted present value of the difference between the favorable lease and the fair market value of the lease.

[13] This may be valued by the cost to reassemble and train the workforce

[14] This may be valued by a reasonable royalty calculation

[15] ASC 805; International Glossary of Business Valuation Terms

[16] Wood, David. “An Unwilling Seller – Is There Such a Thing?” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Page 80

[17] Wood, David. “Personal Goodwill in Search of a Functional Definition.” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Page 40

Pratt, Shannon. Valuing a Business. Fifth Edition. 2008. Page 949

[18] Ibid.

[19] Pratt, Shannon. “Overview of Enterprise and Personal Goodwill.” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Page 46;

Wood, David. “Goodwill Attributes: Assessing Utility.” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Page 98;

LePage, Alexis and Richa Prakash. “Personal Goodwill and Business Goodwill – Are They Marital Assets?” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Page 189;

Burkert, Rod. “Separating Personal and Business Goodwill of Operating Companies in Divorce Valuations.” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Page 276;

Arne, Darrell and James Hamill. “Separating Personal and Business Goodwill.” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Page 378

[20] Pratt, Shannon. “Personal Versus Enterprise Goodwill – Four Examples From My Recent Practice.” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Page 419

[21] Wood, David. “An Allocation Model for Distinguishing Enterprise From Personal Goodwill.” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012.

[22] Wood, David. “Goodwill: Where Are We? How Did We Get Here? What Do We Do About It?” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Page 13;

Burkert, Rod. “Separating Personal and Business Goodwill of Operating Companies in Divorce Valuations.” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Page 278

[23] The hypothetical buyer would, however, have to allocate part of the purchase price to the value of those noncompete agreements.

[24] Niculita, Alina; Angela McKedy and Kimberly Linebarger. “How to Distinguish Personal Goodwill From Enterprise Goodwill, the Key Person Discount, and Noncompete Agreements.” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Page 108

[25] Dietrich, Mark. “Identifying and Measuring Personal Goodwill in a Professional Practice – Part 1: Basic Concepts.” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Pages 342-343

[26] A key person discount relates to the potential of a key individual to become incapacitated, which affects the entire firm value. Personal goodwill relates to the possibility that an individual may leave and compete, which affects the allocation of firm value. While there are similarities between these two concepts, they are, in fact, different.

See Niculita, Alina; Angela McKedy and Kimberly Linebarger. “How to Distinguish Personal Goodwill From Enterprise Goodwill, the Key Person Discount, and Noncompete Agreements.” BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill. Fifth Edition. 2012. Pages 106-107

[27] For example, in cases of marital dissolutions in Texas, the personal goodwill is not a martial asset. Therefore, any personal goodwill would not be divided among spouses in a divorce. Murphy, Kathryn. Business Valuations in Divorce. Dallas Chapter Texas Society of Certified Public Accountants. September 22, 1998. Page 17.