A business has a value equal to the expected future economic benefits to its owner, discounted to a present value. This concept has broad acceptance and appears in multiple economic, finance and valuation texts.

By Jeff Compton, Margaret Bryant and Michael Shapiro

February 07, 2017

Originally published in Texas Lawyer.

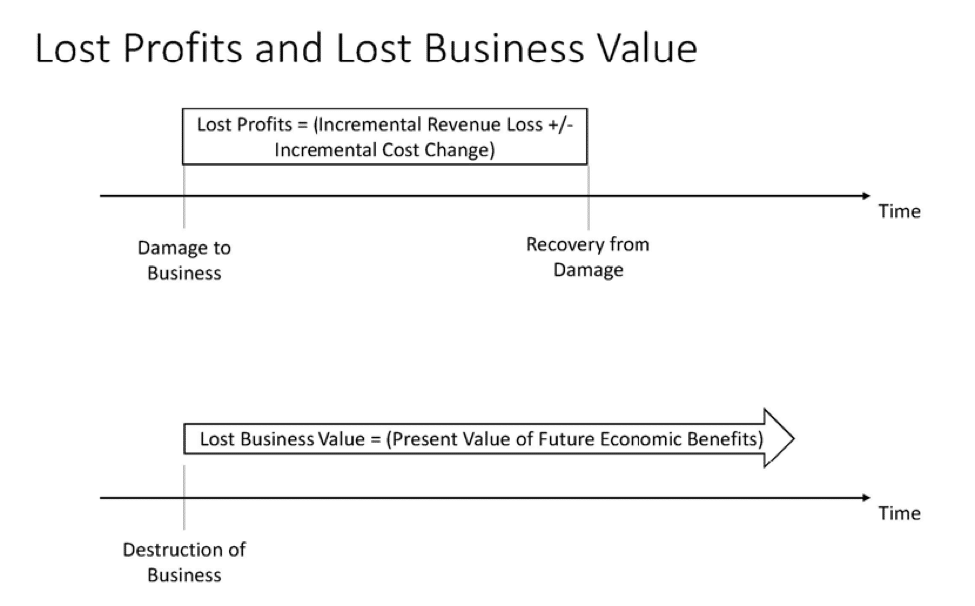

A business has a value equal to the expected future economic benefits to its owner, discounted to a present value. This concept has broad acceptance and appears in multiple economic, finance and valuation texts. See e.g. Damodaran, Aswath, Damodaran on Valuation. 2nd ed., (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2006) at p. 25. Although perhaps similar in concept and application, lost profits represent the incremental change in revenue attributable to a particular action, plus or minus the change in costs arising from that change in revenue (e.g. revenue declined by $10 due to the defendant’s wrongful action but costs declined by $3 due to the same action so the lost profits are $7). See AICPA Practice Aid 06-4, Calculating Lost Profits at ¶ 4. Lost profits must be related to the wrongful action of the defendant which becomes less certain over longer periods as other factors intercede. The diagram below shows the difference in the calculations:

Texas courts recognize the overlap between lost profits and loss in market value damages for businesses in tort and condemnation cases. Generally, lost profits is the proper measure of damages when a business’s activity has been temporarily harmed or interrupted. See Texas Instruments, Inc. v. Teletron Energy Mgmt., Inc., 877 S.W.2d 276 (Tex. 1994). The loss of a business’s market value (also referred to as diminution in value) is usually the proper measure of damages when a business has been destroyed. See Sawyer v. Fitts, 630 S.W.2d 872 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth 1982, no writ). They both account for a business’s profitability but in different circumstances.

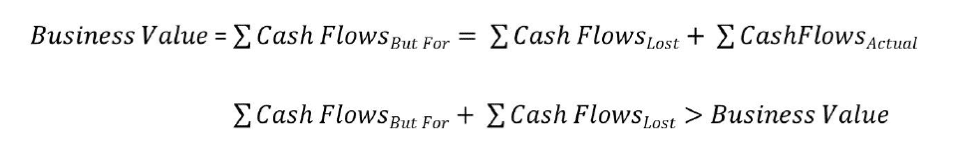

Because of the similarities in the calculations of lost profits and lost business value, confusion can occur as to which applies. Note, however, the present value of future economic benefits includes all revenues and all costs, making the addition of lost profits and lost business value duplicative when the business is destroyed at once. As shown in the equations below, the business value is equal to the discounted sum of all future cash flows but for the damaging act. Adding lost profits to this amount would be double counting that portion of the business value, resulting in an amount that is greater than the value of the business as of the date of damage.

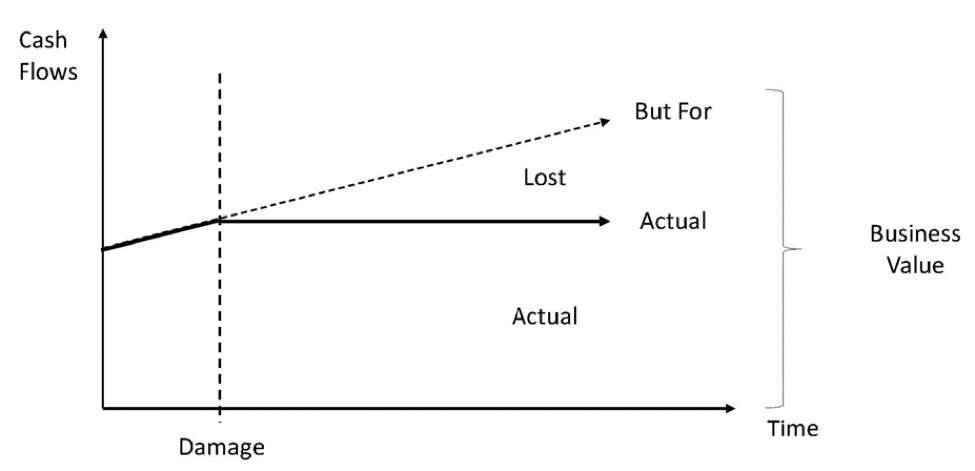

Graphically, this relationship can be seen in the graph below. Adding a lost profits calculation to a lost business value calculation would double count the value graphically represented by the triangular area labeled “lost.”

Due to the overlap, Texas courts have held that awarding both lost profits and the loss of the business’s market value constitutes a double recovery when the injury results in the immediate destruction or cessation of a business. In Sawyer v. Fitts, the roof of the plaintiff’s men’s clothing store collapsed “burying the business with brick, mortar and beams.” The plaintiff sought damages for his lost merchandise and lost profits, among other damages. The Fort Worth Court of Appeals decided that because “the business was completely destroyed, not merely interrupted,” the proper measure of damages was the business’s loss in market value. The court further concluded that the plaintiff could not also receive lost profits because lost profits is a “factor considered in determining the market value of the business.” Other courts have likewise concluded that because “[t]he ability of a business to make a profit is reflected in its market value,” (City of San Antonio v. El Dorado Amusement Co., Inc., 195 S.W.3d 238, 247 (Tex. App.—San Antonio 2006, pet. denied)) an award of the loss in market value of business property fully compensates plaintiffs for the destruction of a business regardless of whether the plaintiff ever rebuilds its business. See State v. Whataburger, Inc., 60 S.W.3d 256, 262 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 2001, pet. denied). Starting a new business to replace the old one does not change the value of the prior, destroyed business and does not allow the addition of lost profits to lost business value.

Texas courts have also indirectly recognized that lost profits and lost business value cannot be recovered for the same injury in their application of the economic feasibility rule. The economic feasibility rule is designed to prevent over compensation. Under the economic feasibility rule, when a business’s loss in market value exceeds the cost to repair the business and lost profits, the measure of damages is the cost of repair and lost profits. But, when the cost to repair the business exceeds the business’s pre-incident market value, the measure of damages is the loss in market value. There is no instance, under the economic feasibility rule, in which a party may recover the loss in the business’s market value and lost profits. See Gilbert Wheeler, Inc., 449 S.W.3d at 481-82; Coastal Transp. Co., Inc. v. Crown Cent. Petroleum Corp., 136 S.W.3d 227, 235 (Tex. 2004).

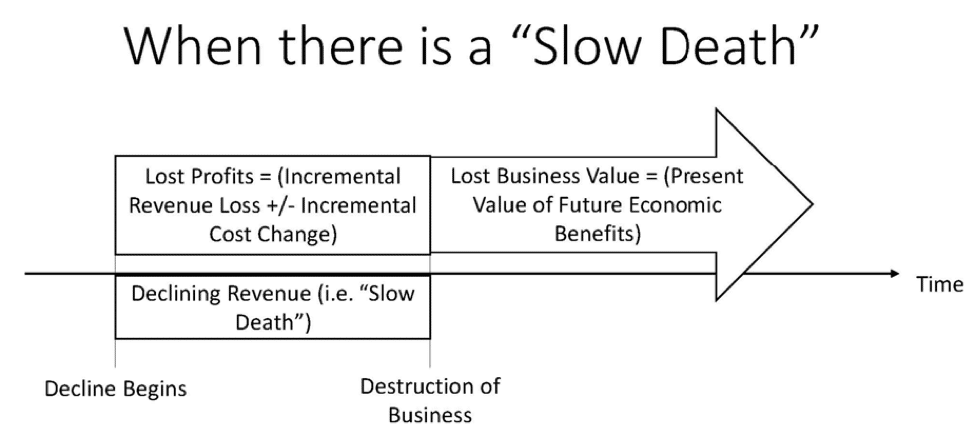

While with a sudden cessation of business, the cash flows used to determine lost profits are duplicative of those used to determine the loss of a business’s market value, the same is not true for a slow decline ending in the cessation of the business. Consequently, lost profits and the loss in business market value may be awarded to the same plaintiff when there is a period in which the business loses profits before it is destroyed. This is the “Slow Death” scenario. There is one condemnation case, City of San Antonio v. Guidry, 801 S.W.2d 142, 150 (Tex. App.—San Antonio 1990, no writ), in which a court effectively recognized the Slow Death scenario. In Guidry, the court upheld an award of lost profits for the period the plaintiff’s restaurant was interrupted by the construction work and the loss in market value after the restaurant closed.

Intuitively, the cash flows preceding the destruction of the business are not those coming after it and therefore are not duplicative. Nonetheless, the longer the lost profits period the more difficult it becomes to project with reasonable certainty. Additionally, a long “Slow Death” period raises concerns about mitigation. Furthermore, a new or untested business that suffers a Slow Death may not be able to recover lost profits. Lost profits “from an activity dependent on uncertain or changing market conditions, or on chancy business opportunities, or on promotion of untested products or entry into unknown or unviable markets, or on the success of a new and unproven enterprise, cannot be recovered” because they are too speculative. Texas Instruments, Inc., 877 S.W.2d at 279.

Thus, generally lost profits and the business’s lost market value are not recoverable by the same plaintiff when a business is destroyed with one exception being the Slow Death scenario.